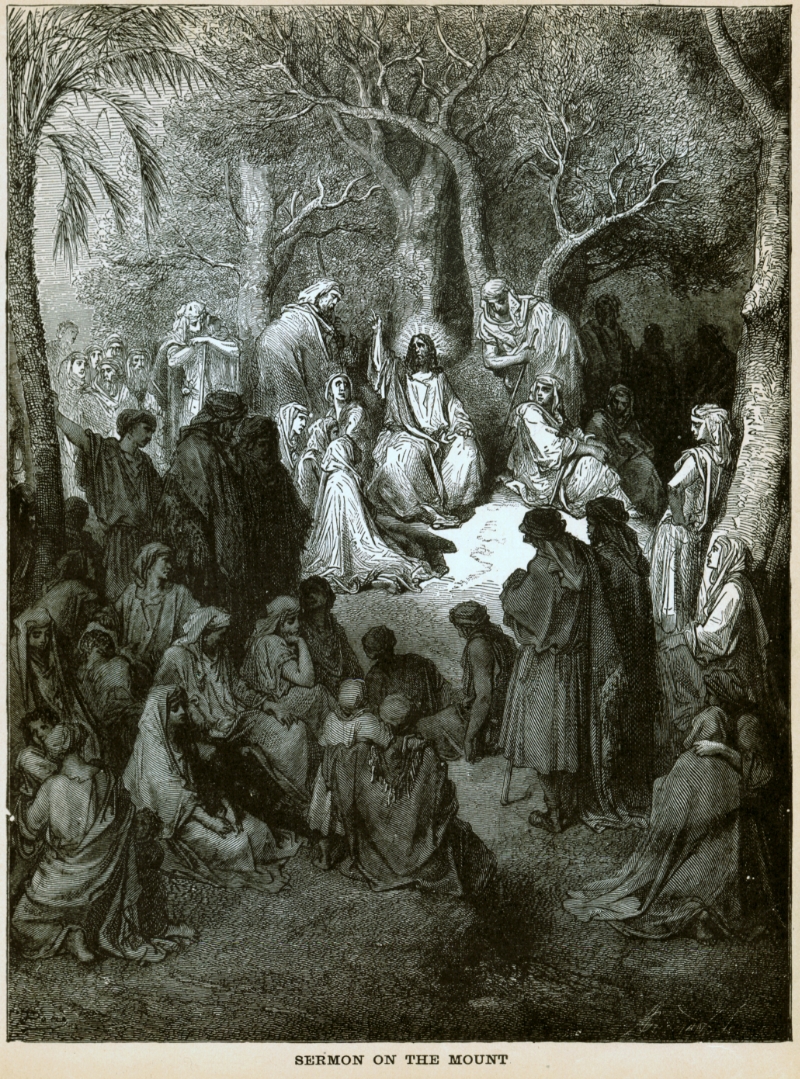

via WikiCommons, CC0.

“You are the salt of the earth; but if salt has lost its taste, how shall its saltness be restored? It is no longer good for anything except to be thrown out and trodden under foot by men.

“You are the light of the world. A city set on a hill cannot be hid. Nor do men light a lamp and put it under a bushel, but on a stand, and it gives light to all in the house. Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works and give glory to your Father who is in heaven" (Mt. 5:13-16).

I am a coward.

No, really. I am. I fear and hate confrontation with a passion that, if instead was directed toward evil, would move mountains and save the world. As opinionated and outspoken as I can be, I usually only voice those opinions with trusted friends. I talk a good game, but can I play ball? Eh... heh.

I write this because I'm seeing our collective cultural insanity coupled with politics-as-usual coming home to our quiet West Michigan town, sending my old devil, anxiety, through the roof. It's hard not to fret.

At some point I may be called to stand up and say, no, that's not right, to be salt and light. And that terrifies me. To quote St. Thomas More in A Man For All Seasons, "This is not the stuff of which martyrs are made."

But God is gentle with the brokenhearted. When he asks of us more than we can give, he will give us what we lack. He is our source of peace.

I know this. But why is it so hard to believe sometimes?

For the sake of Christ, then, I am content with weaknesses, insults, hardships, persecutions, and calamities; for when I am weak, then I am strong (2 Cor. 12:10).