The main character of my work-in-progress is a talented mantua-maker (the 18th century term for dressmaker). Unfortunately, when it comes to fashion, she and I are nothing alike. I am neither a trendsetter nor trend follower, nor do I sew well. In order to write this book, I have not only had to study late 18th century fashion and historical sewing techniques, but I needed to learn how clothing is constructed, simply.

A daunting task. Where to begin?

Vogue Sewing Book

I picked up the 1975 edition of the Vogue Sewing Book at a tiny thrift shop on West Street in Annapolis, fifteen years ago. (I well remember the shopping trip—my husband and I were either engaged or newlyweds and spent a pleasant afternoon wandering downtown Annapolis. Those were lovely days.) I've referenced the Vogue Sewing Book often over the years and especially as I've tackled this writing project.

Among the most important things I've learned from the Vogue Sewing Book: tailoring requires getting... up close and personal. Very personal. This was especially true of the 18th century men's clothing, which was fitted snug against the body, without the aid of Lycra. Tailors were men for a reason!

Man's assemble, circa 1790-1795. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. (Wikimedia Commons)

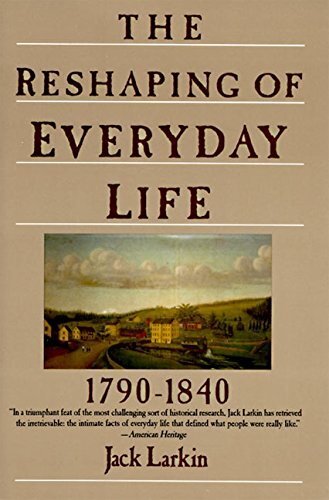

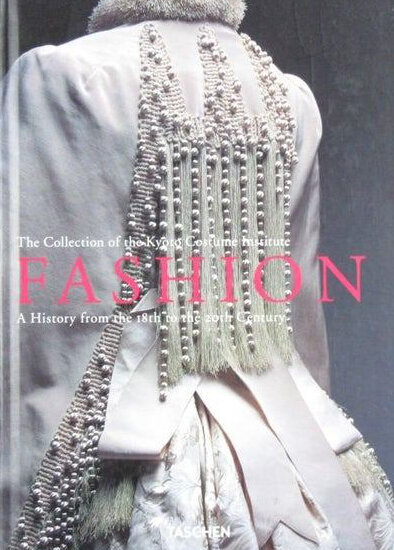

Kyoto Costume Institute

The Kyoto Costume Institute's collection of 18th century artifacts is beyond impressive. While their collection is available for viewing online, I recommend purchasing a copy of their book. The book is coffee table sized and, with its big, glossy photos and lovely close-up shots, is worth the $15 price tag. I refer to this book constantly.

Screenshot of KCI's online archives (1780s-1790s).

American Duchess

Where would I be without the American Duchess Guide to 18th Century Dressmaking? American Duchess makes and sells historical footwear and is well-known in the historical costuming world. This book is mainly an instructional manual on how to sew period costume using period techniques but also includes narrative on the history of each fashion, commentary on materials, and instructions for how to put the bloomin' things on!

The authors also point out some historical inconsistencies with regards gown names. For example, the Italian gown, which was the gown from the mid 1770s through the beginning of the 1790s, sometimes goes by robe à l'anglais. But the English gown, which is an entirely different style that was fashionable earlier in the century, also goes by robe à l'anglais. (Kyoto, for example, uses robe a l'anglais for labeling both.) For me, understanding the difference between the two was crucial.

Also, American Duchess recently released The American Duchess Guide to 18th Century Beauty, which is a companion book totheir dressmaking book. I have not yet purchased it, but oh, I want to! There’s nothing quite like big 18th century hair.

Finally, American Duchess maintains a blog. This post goes over the basic types of 18th century gowns—an excellent primer for us non-experts. And their "Historical Analytics" series has helped me get inside Molly's artistic, dress-designing head.

Big hair, don't care. Portrait of Marie-Antoinette. (Wikimedia Commons)

Redthreaded

Corsets (stays) get a bad rap. The idea that women were restricted in too-tight harnesses, causing them to faint at every turn, is mostly fiction and limited to the 19th century, when steel began to replace whaleboning. No woman in her right mind would put up with being constricted to the point of fainting—not when there's life to live and work to be done. Only vain, silly women tied their laces too tight.

What are stays? Support garments, plain and simple. They kept the girls and the mama belly/spare tires in their proper places, so that gowns fit correctly and lay smoothly. Stays also helped with posture. And like most garments of the 18th century, they were custom fitted to each woman.

To learn more about corsets or to purchase your own, check out Redthreaded. Browsing their site, you'll notice that different centuries have different types of corsets, designed to accommodate the reigning fashions of the day.

Interestingly, while mantua-makers were women, male tailors were in charge of making women's and children's stays. I'm not entirely sure of the reason for this. Tradition?

18th Century Notebook

Another website I reference constantly is the 18th Century Notebook. This site has links to historic examples of not only clothing, but also accessories and common household items. For example: at a few points in the story, we see my male lead character carrying hard coinage. I needed to know what he was carrying his money in. From perusing the 18th Century Notebook, I learned about different kinds of men's wallets, purses, bags, and pockets and was able to make a historically accurate choice.

As it turns out, historical costumers love Instagram. And I'm among their thousands of silent stalkers followers, salivating over their pretty 18th century creations in silk, lace, and ribbon. Using Instagram's "save" feature, I file away any interesting pictures, similar to the way people use Pinterest.

Not surprisingly, many of these costumers are real-life friends with each other. Once you follow one of them, you will eventually figure out who knows who, etc. etc. (Social media is weird.)

When it comes to 1780s and 1790s fashion, my favorite Instagram account is @modernmantuamaker. I also follow @markslauren, @lydiafast, @timetravellingredhead, @alyssagallotte, @fabricnfiction, @before_the_automobile, @makethishistoricallook, @sewstine, @silk_and_buckram, @sew_18thcentury, and (not a costumer) @18th_century_cleophas.

I also follow businesses @americanduchess, @birnleyandtrowbridge, and @redthreaded, as well as the accounts for Mount Vernon (so good!), Colonial Williamsburg, Historic New England, the School of Historical Dress, 18th Century Society, and the DAR Museum.

These people are the 18th century fashion experts, par excellence. Highly recommended.